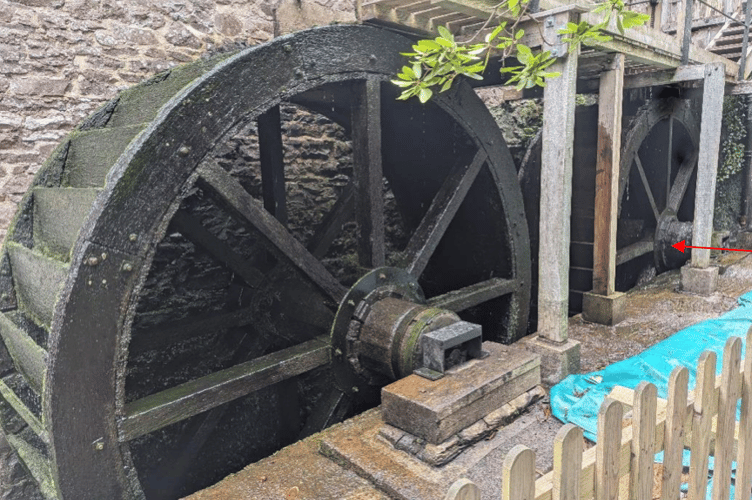

AN oak waterwheel in the grounds of historic Dunster Castle needs repairs before it collapses through decay, Exmoor National Park Authority planners have been told.

The axle of one of the two wheels in Dunster Water Mill has deteriorated and needs to be replaced to allow it to continue as a working mill.

The National Trust, which restored the mill in 1980 and built the waterwheel in 2007, wants to carry out repairs after the current tourism season closes so there would be no impact on the castle and mill.

Spokesman Stephen Hayes said an oak axle on the upper wheel had decayed where the gudgeon, or cruciform, steel passed through its diameter, which sat in a permanently wet environment.

Mr Hayes said the mill was a rare example of a fully operational 18th century grade two starred listed double overshot watermill over three floors.

But he said decay within timber of the upper waterwheel wheelshaft presented a developing structural defect and the trust needed to replace it before it failed.

The proposal was to replace the oak wheelshaft with a decay resistant, sustainably sourced greenheart timber axle of the same dimensions which would significantly outlast oak.

Mr Hayes said: “This change in material will significantly increase the longevity of the waterwheel and reduce the need for future major repairs.

“The benefits of this are numerous, including reduced requirement to fell more oak trees of sufficient size for the axle, less risk to the building from frequent major engineering works, and the savings associated with fewer replacements.

“Aesthetically, the greenheart will be indistinguishable from oak once weathered.”

Mr Hayes said only the axle would be replace with greenheart timber and maintenance and repair of the rest of the components would use English oak due the weight and cost of greenheart.

He said: “Due to the design of the system that connects the axle to the historic machinery, it can be removed without affecting or altering the historic fabric of the building.”

National Trust historical adviser Martin Watts said in a report there had been a grist or corn mill below Dunster Castle working almost continuously since the Middle Ages.

Mr Watts said the survival of two overshot waterwheels in tandem, both of which were still capable of driving machinery and millstones, was nationally important.

He said they were once relatively common in the south west and north west of England, but few double mill layouts now survived in a complete or workable condition.

The continued working of the mill, using waterpower to produce stoneground wholemeal in the traditional way, was also important.

Dunster was one of a small number in Britain which still regularly grind and sell stoneground products to help pay for their upkeep.

Mr Watts said the external appearance of the mill with its timber waterwheels, now comparatively rare in themselves, belied the good quality Victorian cast iron-based machinery of its interior and the continued working and the maintenance of the mill, both aesthetically and mechanically, was considered important.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.